Grikor Mirzaian Suni, composer, conductor, ethnomusicologist, and teacher, was steeped both in his own Armenian folk tradition and, later, European classical music. He was first and foremost a composer of choral music, and creator of scores of vocal solos, and orchestral, operatic, instrumental, and piano works. Some of these are from one-voiced folk material, which Suni rendered polyphonically in four parts. Suni gave harmony to melody in a way that “sounds Armenian” but is also uniquely “Suni.” “Suni’s treatment of the songs was a revelation”; “the harmonization of folk songs…very beautiful”; “never heard more exquisitely shaded chorus work…, Suni’s conducting left nothing to be desired”; (from reviews of his first Philadelphia concert, 1924).

“Suni has composed some of the sweetest lyrical pieces in the realm of Armenian music” (Levon Kazanjian, 1924, Philadelphia). Suni wrote beautiful songs of love, and nature, of his beloved mountains of Karabagh, of their fog, waters, valleys, flowers. He set to music works of great poets of the Armenian language. Some of these may be considered European art songs richly saturated with folk color, belonging in fact to the world of lieder.

Grikor Suni traveled widely in the Russian, Ottoman, and Persian (Iran) Empires, as well as India and finally the United States, directing church choirs, studying folk music, and organizing choruses of Armenian amateur singers for the concert presentation of Armenian music. He elevated and enlivened the cultural life of every place he settled and visited, a unique and inspiring artist dedicated to bringing the common people to the highest artistic level, yet always searching for the best talent.

Grikor Mirzaian Suni was born Grikor Mirzaian on September 10, 1876 in the village of Get•abek•in the old Armenian principality of Gardman, at that time a part of the imperial Russian province of Yelizavetpol (the former khanate of Ganja, Arm.: Gandzak• before the Russian occupation in 1805). From age two to fifteen, Grikor lived in Shushi, a district capital in the Karabagh (Arm.: Gharabagh) region. He came from a line of musicians documented back to his great grandfather, the ashugh (minstrel) Teymur, Melik Hovhaness Mirzabek•ian (c.1775). Suni’s grandfather was the ashugh Dadasi, and his father was folk poet/singer and miniature painter Hovhaness Varandetsi. Grikor also painted miniatures, and liked to illustrate his song titles. He was probably descended from princes of the ancient Armenian kingdom of Siunik, thus used the name Suni (pronounced “Siuni”).

Grikor Mirzaian Suni was born Grikor Mirzaian on September 10, 1876 in the village of Get•abek•in the old Armenian principality of Gardman, at that time a part of the imperial Russian province of Yelizavetpol (the former khanate of Ganja, Arm.: Gandzak• before the Russian occupation in 1805). From age two to fifteen, Grikor lived in Shushi, a district capital in the Karabagh (Arm.: Gharabagh) region. He came from a line of musicians documented back to his great grandfather, the ashugh (minstrel) Teymur, Melik Hovhaness Mirzabek•ian (c.1775). Suni’s grandfather was the ashugh Dadasi, and his father was folk poet/singer and miniature painter Hovhaness Varandetsi. Grikor also painted miniatures, and liked to illustrate his song titles. He was probably descended from princes of the ancient Armenian kingdom of Siunik, thus used the name Suni (pronounced “Siuni”).

Suni began studies in 1883 in the parish school, the same year his father fell off a horse and died. In 1885, the Russian tsar, fearful of the growing nationalism of the non-Russian peoples, ordered all Armenian parish schools closed, breaking the promise of the decree of 1836 which allowed Armenian self-education. Though the schools reopened after one year, these actions spurred the creation of the first Armenian revolutionary groups, which Suni later joined.

In Shushi, Suni learned Armenian music notation, khaz, from Father Garegin Hovhanessian, student of Nik•oghaios Tashj•ian, grandstudent of Baba Hampartsoum Limonjian, creator of these l9th century khaz, (1813). European music notation was still unknown, and music was passed down through the oral tradition. There had been a medieval liturgical khaz system whose code was by then lost, so the 1813 khaz were the only tools available to notate music.

As his great musical ability had already been recognized, in 1891 Suni left home and began studies in Echmiadzin, seat of the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, near Armenia’s current capital of Yerevan. Based there at the Gevorgian Academy, Suni worked with the major teachers of Armenian music, first with Sahak• Amt•uni, then Krist•opor K•ara-Murza, then Soghomon Soghomonian, later known as K•omit•as Vardap•et• (priest). During summers, Suni took private lessons in Tiflis (Tbilisi, Georgia) with Mak•ar Yek•malian, pioneer in setting the Armenian liturgy polyphonically (first published 1896).

K•ara-Murza imparted to Suni great love for folk song, and introduced European musicology and polyphony. The churchfathers, however, were used to singing with one vocal line alone (“One God: one voice”), and eventually harmony instructor K•ara-Murza was told, “The walls of Echmiadzin are not wide enough for your ideas.” Moreover, K•ara-Murza was siding with the students in a dispute over the running of the seminary, so he was dismissed. The young Suni was already witness to much controversy.

Working then with K•omit•as, Suni began formally gathering traditional and religious melodies, listening to the people, and writing down in khaz notation eventually hundreds of folk songs, a calling which he followed for decades. Suni and K•omit•as were close colleagues and friends working together on the passion of those times, preserving folk music with a goal of organizing mixed choruses for concert presentation.

Upon graduating in 1895 from the Gevorgian Academy, Suni returned to his native Shushi, formed a chorus, and presented his first concert of his own arrangements of Armenian folk songs. This debut was celebrated forty years later all through the Armenian world. Its success propelled Suni’s next stage of study, in St. Petersburg where he moved in autumn 1895, and remained for almost a decade.

Upon graduating in 1895 from the Gevorgian Academy, Suni returned to his native Shushi, formed a chorus, and presented his first concert of his own arrangements of Armenian folk songs. This debut was celebrated forty years later all through the Armenian world. Its success propelled Suni’s next stage of study, in St. Petersburg where he moved in autumn 1895, and remained for almost a decade.

Now in the capital of the empire, Suni took private lessons in music theory and composition for three years, preparing for entering, in 1898, with a scholarship, the theoretical composition class of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov at the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music. He studied also with Alexandr Glazunov and Anatolii Liadov, graduating in 1904.

Here Suni learned orchestration, encountered and mastered the piano, wrote fugues, and became close to Rimsky-Korsakov, who even asked advice of the young musician from the Caucasus when he wanted “oriental sounding” orchestration. As Rimsky-Korsakov and colleagues were also deeply interested in folk music, these study years nurtured a happy amalgam of Suni’s national pride and musicianship. Suni arranged folk songs, composed patriotic songs and choruses, and also composed a series of romances, which received the high appraisal of his teacher. His first folk song collection was published in 1904.

From 1899, Suni was director of the Armenian Church choir, teaching the new Yek•malian liturgy along with his own polyphonic liturgical settings. Rimsky-Korsakov especially liked two of these, and would come to the church to listen, “with tears in his eyes.” Eighty-some years later, Yerevan professor Robert Atayan was surprised to discover in the Echmiadzin library an unknown Suni liturgical manuscript, “Miashabat Or Hangust•yan” (Sabbath Repose), with words by 12th century poet/theologian Nerses Shnorhali. This work, which Atayan analyzed and published in the 1987 Echmiadzin Journal, is scored for three-part male choir plus solo tenor, with brief additions of three-part, then two-part children’s choir, yielding at one point seven-part polyphony, especially impressive for Suni’s time. “This is a unique input into Armenia’s classical compositional heritage,” says Atayan, who was at the forefront of the rediscovery of Suni’s contributions.

In 1902, Suni won first prize for the best musical drama of Bab (in Russian), by Isabella Grinevski, produced by the Theatre Art of St. Petersburg. Bab was later banned. St. Petersburg had a lively Armenian student life, and Suni participated fervently. He founded and directed a chorus and an instrumental folk song group, and organized concerts and student events. He married Tiflis-Armenian university math student Nvart Sonyants. The first three of their eight children were born there.

In 1902, Suni won first prize for the best musical drama of Bab (in Russian), by Isabella Grinevski, produced by the Theatre Art of St. Petersburg. Bab was later banned. St. Petersburg had a lively Armenian student life, and Suni participated fervently. He founded and directed a chorus and an instrumental folk song group, and organized concerts and student events. He married Tiflis-Armenian university math student Nvart Sonyants. The first three of their eight children were born there.

Those St. Petersburg years saw political and social turmoil, as interest in democracy, and liberal and socialist ideas grew. Suni was present at the January 9, 1905 Tsarist massacre of demonstrators called “Bloody Sunday.” In the aftermath, Rimsky-Korsakov was dismissed from the conservatory for his support of students’ rights, and his concerts were banned, a ban which extended to the provinces .

In 1904 Suni was asked by the Russian Imperial Music Society to travel in the Caucasus and Russia to collect folk music and organize concerts. His first concert was back in Shushi, probably in the summer of 1905. Immediately after the concert the imperial power forbade him to appear publicly.

So in 1905 Suni accepted the invitation to teach in Tiflis, the largest city in Transcaucasia, at the Nersissian School, where he took the place of (now deceased) Yek•malian, directed the monastery choir, and was a highly esteemed teacher. In 1903 the Tsarist government in Transcaucasia had seized the properties of the Armenian Church, stimulating the revolutionary organizations to resist. Suni joined the struggle, and by 1908, during a full-scale repression, had to flee with his family to Turkish Armenia, where the recently established Young Turk government promised a more tolerant and constitutional regime.

Now a member of the Dashnak•sutiun, the major Armenian revolutionary party working against Ottoman and Russian imperial oppression of Armenians, Suni was both a musician and a political activist. He was writing patriotic and political songs, including at least twenty marches, some of which were adopted as Dashnak• hymns, many of which he left unsigned. For Grikor Suni, music was not only high art, but a living part of the revolutionary struggle against autocracy. His commitment to political activism resulted in his music being repressed wherever his politics were out of favor. Ultimately his music was lost for a generation.

While in Turkish Armenia, Suni organized and directed choruses and taught in T•rap•izon, Samson, K•irason, and elsewhere. During these years he devoted particular attention to the collection of Armenian musical legends, as well as folk songs, studying the elements of Armenian music that give it its specific character. Still living on the Ottoman side of the border, he moved in 1910 to Erzurum (Arm.: Garin), the largest city in the Eastern Anatolian peninsula, and taught until 1914 at the Sanassarian school. Here he composed the “Erzurum March” of which city officials were quite proud. When World War I broke out, with Russia and Turkey enemies, and Suni a Russian subject in Turkey, the family was awakened in the night by an official, and warned to flee for their lives back to the Russian side of the border. Suni attributed this act of humanity to the appreciation for his “Erzurum March.” In gratitude, he began many concerts thereafter with that march. The Mirzaian-Suni family reached Tiflis in safety, and remained there until 1922.

During World War I, Suni conducted the Symphony Orchestra of Tiflis, and founded an Armenian opera company. He composed the operas Aregnazan (1906, text from Ghazaros Aghayan) and Art•avazd II, the operettas Asli-Kyaram (Asli Keram) (libretto by Suni) and Motsik•ool, stage music for Levon Shant’s Hin Ast•vatsner (Ancient Gods), and also orchestral works including Symphony in C Minor, and the suites Sketches of Van, and Orientale (Arevelkoom). He created orchestral accompaniments to choral, solo, and liturgical works, and orchestral arrangements of other composers’ works, including G.O. Korganov’s piano work, Bayati: Fantasia on Caucasian Themes, and V. Valentinov’s operetta, Secrets of the Harem. He wrote a history of Armenian music and the theory of Persian music, poems and essays (“What is art?”). He founded the Society of Armenian Music Theoreticians, working with musicians Sp•iridon and Romanos Melikian, Anushavan T•er-Ghevondian, Krist•apor Kushnarian, ethnographer Garegin Levonian, and the great poet Hovhaness Toumanian, Suni’s close friend and neighbor.

During World War I, Suni conducted the Symphony Orchestra of Tiflis, and founded an Armenian opera company. He composed the operas Aregnazan (1906, text from Ghazaros Aghayan) and Art•avazd II, the operettas Asli-Kyaram (Asli Keram) (libretto by Suni) and Motsik•ool, stage music for Levon Shant’s Hin Ast•vatsner (Ancient Gods), and also orchestral works including Symphony in C Minor, and the suites Sketches of Van, and Orientale (Arevelkoom). He created orchestral accompaniments to choral, solo, and liturgical works, and orchestral arrangements of other composers’ works, including G.O. Korganov’s piano work, Bayati: Fantasia on Caucasian Themes, and V. Valentinov’s operetta, Secrets of the Harem. He wrote a history of Armenian music and the theory of Persian music, poems and essays (“What is art?”). He founded the Society of Armenian Music Theoreticians, working with musicians Sp•iridon and Romanos Melikian, Anushavan T•er-Ghevondian, Krist•apor Kushnarian, ethnographer Garegin Levonian, and the great poet Hovhaness Toumanian, Suni’s close friend and neighbor.

The Russian Revolution and Civil War marked this period, in the latter part of which Suni traveled to Tehran (1919-1920), India, Egypt, and Constantinople. In October 1919, the government of the first republic of Armenia (1918-1920) invited Grikor Mirzaian (Suni) to be the founder of a national conservatory of music. At that time, the railroads were blocked by military actions, so Suni probably could not reach Yerevan. In 1921, the Communists took over Tiflis, and by 1922, Suni was targeted as a political enemy, so that after he finally was able to return to Tiflis, he had to flee, with his large family, to Istanbul (then still commonly called Constantinople). He had to leave behind the trunk full of his precious music scores with the family of Hovhaness Toumanian, whose poetry Suni had set to music. Suni intended to return, but was never able to, and that trunk still has not been found.

Suni spent almost two years in Istanbul where he organized an Armenian cultural/musical society, gathering to his home musicians and writers, including Vahan Tekeyan. He conducted the Scutari coed choir and taught at six Armenian schools, Gentronagan (Getronagan), Yessaian, Berberian, Hintlian, Bezazian, and Karageozian, many with children orphaned by the 1915 Ottoman Turkish state genocide of its Armenian subjects.

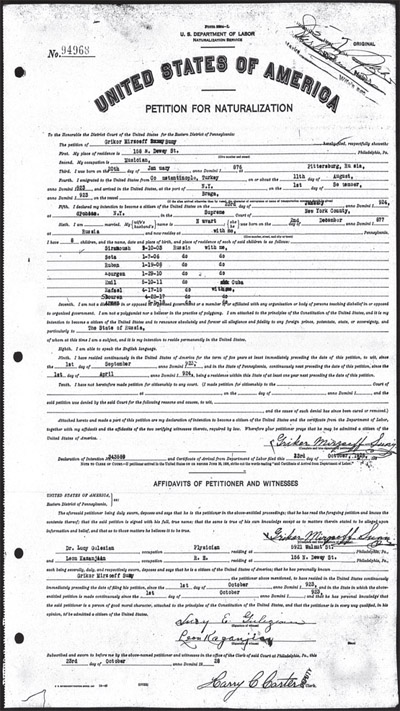

In this period, Suni wrote in a letter, “The Kemalist alarm is approaching.” As an Armenian in an ominously changing Turkey, in 1923, he was forced again to flee. This time, he moved his family to the safety of America.

The Armenian Church of America brought Suni to create church choirs. After a brief stay in New York, he began work with choirs in five Boston area churches. In 1925, he moved to Philadelphia, his final home. He conducted church choirs, and organized folk choruses, presenting concerts from the start, winning much acclaim. In 1925 and 1935 in Boston’s Symphony Hall, the Suni-led Armenian chorus won first prize in the inter-ethnic competition for best folk music examples, and in 1933, second prize at the Chicago exposition competition. Suni directed “Suni Choruses” around the U.S., including New York, Boston, Worcester, Providence, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Chicago.

Through correspondence, Suni kept in close touch with his colleagues abroad. He heard how life was in the new Soviet Armenia, and that Armenian cultural arts were being supported. He decided to support Soviet Armenia and join the Communist Party. His colleagues in Yerevan implored him to return home to head the Yerevan Conservatory of Music. Though Suni’s desire was to return to Armenia, it was never to be, for it was impossible as long as Armenia had no insulin for the now diabetic Suni. Suni helped all he could from a distance by sending music, instruments, letters, and by publishing in 1934 in New York a song collection, Nor K•yanki Yerger (Songs for a New Life).

In 1935, the fortieth anniversary of his musical debut was celebrated in the U.S. and in Soviet Armenia with jubilee concerts, and the formal organizing of the U.S. Suni choruses as the Armenian Musical Society of America. Soviet Armenia published a volume of ten of his works for voice and piano.

The Church, and also his former associates in the Dashnak• Party now rejected him for having joined the Communists. Then, in 1937, at the time of the political purges in the Soviet Union in which hundreds of thousands of innocent people perished, Suni made a public criticism of Joseph Stalin. The news traveled back to Armenia, Suni was rejected by the Soviet regime, and his music was repressed for decades. In the evolution of Armenian music, a bright, guiding light was blocked, then largely forgotten.

In his last years, until his death on December 18, 1939, Suni found some Armenian doors closed to him, so he had to transliterate works into Russian for the Russian chorus that would still work with him. Still, he remained enthusiastic until the end. In the 1940s, his children and students, with Philadelphia physician Dr. Lucy E. Gulezian, published four volumes of his songs called Armenian Song Bouquet. Among those continuing with his music were his son Gourgen (George) Suny, conductor of the Philadelphia Suni Chorus; his daughter Seda Suny, dance teacher in New York; and his student Harutiun Samuelian, conductor of the New York Suni Chorus.

Grikor Suni was in the group of artist musicians who documented and developed Armenian music. He was, for Armenian classical music, one of the most renowned, indeed charismatic, prolific, and hardworking figures. He was a master of the small song, melody, harmony, counterpoint. He reveled in polyphony where it earlier had been forbidden. As in his politics and personal life, in music, Suni expressed himself honestly and freely, and made tangible contributions to Armenian music, and indeed, to world music.

Much of Grikor Suni’s music is still unpublished, nearly all out of print, and unrecorded. This body of work is waiting to be opened up. Some of the manuscripts are in Yerevan, in the Charents Museum, and some are in the Ann Arbor archive of the Suni Project: Music Preservation. And some are in that, now legendary, trunk in Tbilisi.